Exercise, Depression, and the Gap Between Evidence and Capacity

Marsha Sakamaki • January 24, 2026

Short notes on health, aging, and prevention.

No noise. No selling. Ever.

What exercise research shows when starting is the hardest part

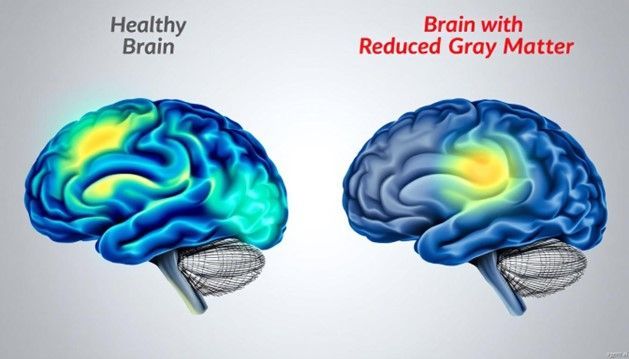

Exercise has long been associated with improved mood and mental health. What continues to evolve is how well exercise holds up when examined alongside standard treatments for clinical depression, rather than being treated as a lifestyle add-on.

A recent update to a large Cochrane meta-analysis reviewed 69 randomized controlled trials involving nearly 5,000 participants with depression. The authors compared structured exercise programs with no treatment, usual care, psychotherapy, and antidepressant medications. Their conclusion was measured. Exercise reduced depressive symptoms compared with no treatment, and when compared directly with therapy or medication, the effects were similar. Exercise was not superior, but it was not inferior.

That conclusion does not suggest exercise should replace therapy or medication. It does reinforce that exercise belongs in the category of legitimate mental health support rather than optional self-care.

The authors were careful about limitations. Exercise trials cannot be blinded in the way drug trials can. Expectations, attention, routine, and social engagement likely contribute to some of the observed benefit. Publication bias remains possible, and long-term follow-up data are limited. When these factors are taken into account, the estimated benefit of exercise is reduced, but it does not disappear.

The evidence points to a consistent, moderate effect rather than a dramatic one.

Where the findings become especially relevant is in the gap between evidence and practice. A large proportion of people with major depressive disorder do not meet basic physical activity guidelines. When activity is measured objectively rather than by self-report, actual movement levels are even lower. Knowing that exercise can help is not the same as being able to start or sustain it, particularly when depression, pain, fatigue, illness, or age are involved.

This is where exercise stops being a simple recommendation and becomes a capacity problem.

I use the term 7 Daily Essentials to describe the foundations that support long-term health and resilience:

- Oxygen

- Water

- Sleep

- Good food

- Nutrition

- Exercise

- Optimism

These essentials are not binary. They are not “on” or “off.” Each exists on a continuum, and capacity can vary widely from person to person and from one phase of life to another.

Exercise fits into this framework in the same way. For someone who is already active, it may look like walking, resistance training, or structured aerobic workouts. For someone who is depressed, deconditioned, injured, or overwhelmed, those same recommendations may be unrealistic at the start. That does not make exercise irrelevant. It means the entry point has to change.

Low-barrier forms of movement can help bridge this gap. Short, structured sessions that activate muscles, circulation, and the nervous system allow the body to engage in movement without requiring endurance, motivation, or complex planning.

In practical terms, these approaches can:

- provide brief but repeatable exposure to movement

- reduce the cognitive and emotional load associated with starting

- support circulation, posture, and sensory input

- create structure when energy and motivation are limited

They are not substitutes for comprehensive exercise programs, and they are not treatments for depression. Their role is supportive. They allow the exercise essential to be met imperfectly when perfect adherence is not possible.

Vibration platforms such as Power Plate or V-Max fall into this category when used intentionally. They offer short, repetitive muscular activation and sensory stimulation that some people can tolerate when other forms of exercise feel out of reach. For some, they serve as a starting point. For others, they complement walking, strength training, or other activities.

The Cochrane review does not point to a single optimal exercise modality, intensity, or protocol. Benefits were observed across a wide range of intensities, from very light to vigorous, and across aerobic, resistance, and combined approaches. This suggests that consistency and feasibility matter more than precision.

Exercise should not be framed as a cure for depression, and it should not be used to diminish the value of therapy or medication when those are needed. It does deserve to be treated as part of the foundation of mental and physical health, alongside the other daily essentials. When starting is difficult, reducing barriers matters more than optimizing technique.

That is the purpose of this article. Not to promote a specific tool, but to clarify how exercise fits into health in the real world, where capacity varies and progress is rarely linear.

If you want to explore how exercise fits into the broader framework of daily health needs, you can read more about the 7 Daily Essentials here. Information about low-impact movement options, including vibration platforms, is available here as well. Both are offered as context and support, not prescription.